The visitor's center at Microsoft's headquarters campus in Redmond, Washington. (Photo: Stephen Brashear/Getty Images, via Microsoft)

The visitor's center at Microsoft's headquarters campus in Redmond, Washington. (Photo: Stephen Brashear/Getty Images, via Microsoft)With the U.S. midterm elections on Nov. 6 fast approaching, Microsoft says it's gone to court to seize control of six domains that it's tied to the APT group known as "Fancy Bear." Also known as APT28, Group 74, Pawn Storm, Sofacy, Strontium and Tsar Team, the hacking group is widely believed to be run by Russia's military intelligence service, known as the GRU.

See Also: Dismantling Bot Armies With Behavioral Biometrics

Microsoft President Brad Smith says his company's Digital Crimes Unit successfully seized the six domains last week after applying for a court order to do so. "As a special master appointed by a federal judge concluded in the recent court order obtained by DCU, there is 'good cause' to believe that Strontium is 'likely to continue' its conduct," Smith said.

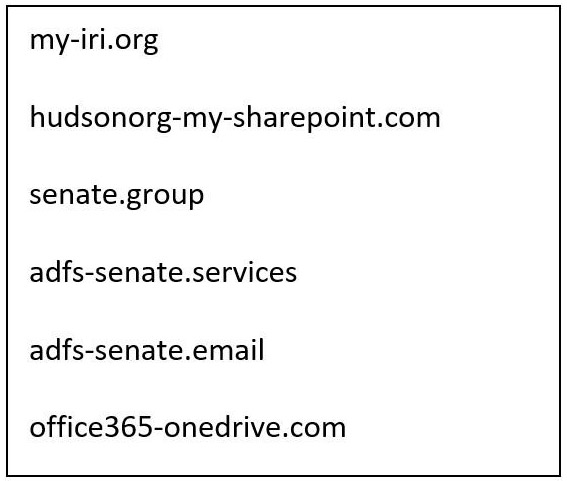

The six domains seized last week by Microsoft, which it says appear to be part of active Fancy Bear attack campaigns.

The six domains seized last week by Microsoft, which it says appear to be part of active Fancy Bear attack campaigns."We currently have no evidence these domains were used in any successful attacks before the DCU transferred control of them, nor do we have evidence to indicate the identity of the ultimate targets of any planned attack involving these domains," Smith said in a Monday blog post.

But he said that the domains being used by the group suggest that Fancy Bear is expanding its target list, after having already directly targeted the staffs of two senators earlier this year (see Fancy Bear Targets US Senate, Security Researchers Warn).

One of the domains, for example, mimics the International Republican Institute, "which promotes democratic principles and is led by a notable board of directors, including six Republican senators and a leading senatorial candidate," he said. The group has also continued to issue warnings about Russian interference in other countries' elections.

Another one of the seized domains mirrors one used by the Hudson Institute, a conservative think tank headquartered in Washington that regularly hosts discussions on defense and technology matters, including cybersecurity.

Microsoft's Repeat Legal Maneuver

This isn't the first time that Microsoft has gone to court to seize domains that it believes are being used by Fancy Bear as part of its attack campaigns (see Microsoft Battles Fancy Bear Hackers - With Lawyers).

"We have now used this approach 12 times in two years to shut down 84 fake websites associated with this group," Smith said. "Attackers want their attacks to look as realistic as possible and they therefore create websites and URLs that look like sites their targeted victims would expect to receive email from or visit. The sites involved in last week's order fit this description."

Attack infrastructure and decoy websites tied to Fancy Bear have previously been used to target not only U.S. senators, but also the Democratic National Committee, the Democratic National Convention Committee, candidates in Germany and France, the Turkish and Montenegro parliaments, the World Anti-Doping Agency and nuclear power generator Westinghouse Electric Company, among many other targets.

US Mid-Term Election Looms

The timing of the latest seizure of active Fancy Bear domains shows that whatever steps the U.S. government might be taking to counter Russian election interference, there's evidence that Moscow-driven information warfare and propaganda campaigns are continuing (see How Trump Talks About Russian Hacking).

"We're concerned that these and other attempts pose security threats to a broadening array of groups connected with both American political parties in the run-up to the 2018 elections," Smith said.

The GRU has already been tied to hack attacks against the DNC and DNCC, among others, and accused of not only hacking into the DNC's Microsoft Exchange Server but also running spear-phishing attacks against Democratic officials' webmail accounts and then leaking stolen emails and documents (see Nation-State Spear Phishing Attacks Remain Alive and Well).

Last month, the U.S. Justice Department indicted 12 Russian intelligence officers for attempting to interfere in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. The federal indictment called out two GRU units by name - 26165 and 74455 - as well as listed their commanding officers and team members (see 10 Takeaways: Russian Election Interference Indictment).

US Government's Response

If Russian information warfare campaigns designed to interfere in the political systems of other countries - including the U.S. - are continuing unabated, it's not clear whether sufficient steps are being taken to stop them (see Redoubling Efforts to Secure Midterm Election).

In June 2017, DHS officials told Congress that in 2016, attackers had probed 21 states' networks and websites, including in some cases election systems, and successfully hacked at least one state - Illinois - to steal 86,000 voter records.

Despite U.S. intelligence chiefs warning in public testimony before Congress that Russia's interference attempts have not diminished at all since 2016 - leaving the suggestion that they may in fact have increased - the Trump administration didn't begin issuing strong statements about election security until earlier this year.

In February, Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen M. Nielsen said that the Department of Homeland Security had been working with "federal, state and local partners ... for more than a year to bolster the cybersecurity of the nation's election infrastructure." Efforts included "reading in" up to two officials in each state, so they could receive threat intelligence.

Many states have been adopting more secure voting machines or switching to paper ballots. The latter approach is widely lauded by cryptography and information security experts as being the most secure and trustworthy approach available.

Some secretaries of state, however, have criticized the DHS effort as being too little, too late, and say they are receiving no guidance on countering Russian propaganda campaigns (see States Seek Federal Help to Combat Election Interference)

In March, Nielsen told a Senate committee that some of the election security improvements being touted by DHS might not be in place until the run up to the 2020 elections. She also revealed that at that time, only 20 state officials had the necessary clearances to begin receive the intelligence briefings (see Will Congress Lose Midterm Elections to Hackers?).

Tools from Google, Microsoft

In the bigger picture, information security experts say that too many candidates and party officials remain vulnerable to online attacks.

Speaking at last week's ISMG Security Summit in New York City, Ed Amoroso, the former CSO of AT&T who's now head of consultancy TAG Cyber, asked why major U.S. presidential candidates will get assigned a U.S. Secret Service physical protection detail, while still having their IT systems and information security get administered by a campaign worker who majored in political science and graduated in the past 12 to 24 months.

To help, both Google and Microsoft have announced programs and tools that are designed to protect individuals, communications as well as websites that provide election information. Both of the companies' programs are predicated on individuals and organizations using each of the company's products.

Google's Advanced Protection Program

Some setup may be required. Google's Advanced Protection program, which the company says is designed to help safeguard "anyone at risk of targeted attacks, like journalists, activists, business leaders and political campaign teams," requires users to purchase two security dongles.

"Yes, security keys can be inconvenient, but this is what will save you," Huntley says - at least, potentially, on Google or anywhere else you're able to use such technology," says Shane Huntley, who's part of Google's threat analysis group, via Twitter.

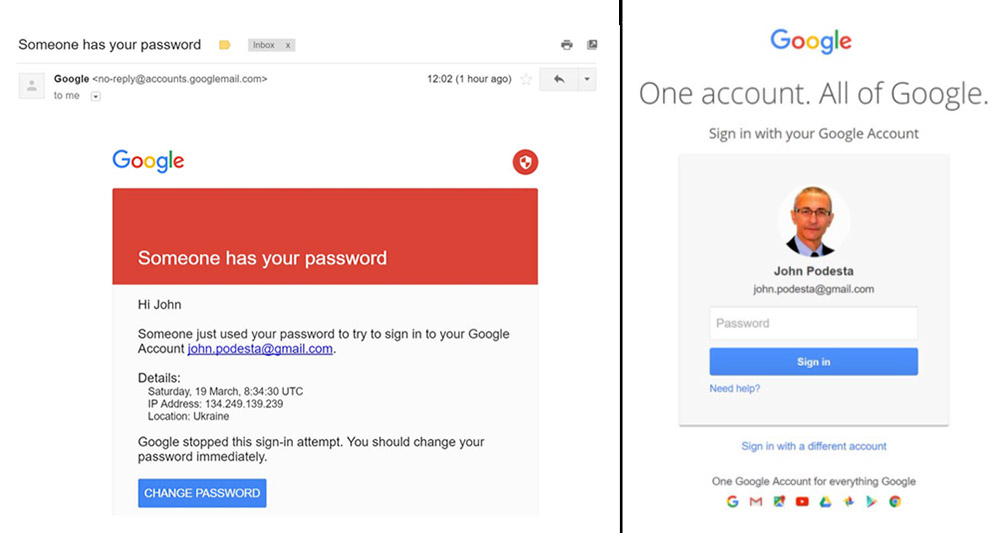

The phishing attack against John Podesta, who managed Hillary Clinton's 2016 presidential campaign, used an email with a "Change Password" link, on left, that led to a Bit.ly link that resolved to a fake Google Account log-in screen, on right. (Source: Pwn All The Things, via WikiLeaks dump of Podesta's emails.)

The phishing attack against John Podesta, who managed Hillary Clinton's 2016 presidential campaign, used an email with a "Change Password" link, on left, that led to a Bit.ly link that resolved to a fake Google Account log-in screen, on right. (Source: Pwn All The Things, via WikiLeaks dump of Podesta's emails.)Google also offers a Protect Your Election program, which is designed to ensure the availability of websites as well as to protect accounts, for example via strong authentication and limits on third-party access to emails, contacts and Google Drive files.

In May, Google parent Jigsaw began offering a distributed denial-of-service attack defense tool called Project Shield for free to political organizations, campaigns and candidates.

Microsoft's AccountGuard

In April, Microsoft announced the launch of its Defending Democracy Program. At the RSA Conference in San Francisco the same month, Microsoft President Brad Smith said the program is designed "to protect candidates, campaigns, voters and voting equipment."

On Monday, Microsoft said it was expanding that offering via its AccountGuard, which requires organizations and individuals to already be using Microsoft's Office 365 productivity software.

The service is designed to offer threat detection - "including attacks by known nation-state actors - and notifications for users' work and personal accounts, as well as to provide security guidance and education, says Tom Burt, who heads Microsoft's customer security and trust group, in a blog post.

Burt says the offering is free for all federal, state and local office candidates in the U.S., as well as sitting members of Congress and national and state party committees, as well as certain technology vendors and nonprofit organizations who support campaigns and committees.

He says the AccountGuard is based on previous work Microsoft has done to help protect election security, including its support for the Iowa caucuses in 2016, as a technology supplier to both major U.S. parties' conventions, as well as Microsoft's Washington, D.C.-based office.

More Work Required

Both Google and Microsoft say that while their offerings are intended to help address election security, much more needs to be done.

"We must work on the assumption that these attacks will broaden further," Microsoft's Smith said. "An effective response will require even more work to bring people and expertise together from across governments, political parties, campaigns and the tech sector."